FOCUS ON Osteoarthritis

Download the 4-page Focus on: Osteoarthritis PDF

APhA gratefully acknowledges the financial support from Sanofi US Services, Inc., for the development of this resource, Focus on Osteoarthritis: Pharmacists Helping Patients Maximize Function. The following individuals served as APhA content developers and pharmacy practice advisors:

Leticia A. Shea, PharmD, BCACP;

Kelly Brock, PharmD; and Theodore Pikoulas, PharmD, BCPP.

Although every reasonable effort is made to present current and accurate information for public use, APhA and its employees and agents do not make any warranty, guarantee, or representation as to the accuracy or sufficiency of the information contained herein, and APhA assumes no responsibility in connection therewith. The information referenced in the document is provided “as is” with no warranties of any kind. APhA disclaims all liability of any kind arising out of the use of, or misuse of, the information contained and referenced in this document. The use of information in this document is strictly voluntary and at the user’s sole risk.

Prevalence

- An estimated one in five adults in the United States has been diagnosed with arthritis.1

- OA is the most common form of arthritis and ranks among the top three health conditions causing disability.2,3

Clinical Manifestations of OA

- OA involves the release of inflammatory mediators by cartilage, bone, and synovium, and has been linked to many health conditions, including increased risk for cardiovascular disease.4-6

- Symptoms include pain, swelling, and stiffness in the affected joints.

The Vicious Cycle of OA

- Patients with OA often experience reduced mobility and challenges performing activities of daily living.

- Patients often become sedentary and gain weight.

- Worsening mobility impairs patient function and further contributes to undesirable health conditions.

- Physical impacts may include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and some types of cancer.

- Mental and psychological impairments may include depression, anxiety, and decreasing cognitive function.7

In addition to having difficulty with function and mobility, patients with OA may have challenges with treatment, including:

- Identifying and accessing appropriate treatment options.

- Understanding the risks and benefits of pain medications.

- Adhering to a pain management treatment plan.

- Being at risk for the misuse or abuse of pain medications.

Research has found that involving pharmacists in the care of patients with OA can improve utilization of treatments, function, pain, and quality of life for their patients.8 Pharmacists can help patients:

- Navigate treatment options.

- Establish and attain functional goals.

- Minimize factors that may lead to poor health outcomes.

- Adhere to treatment recommendations.

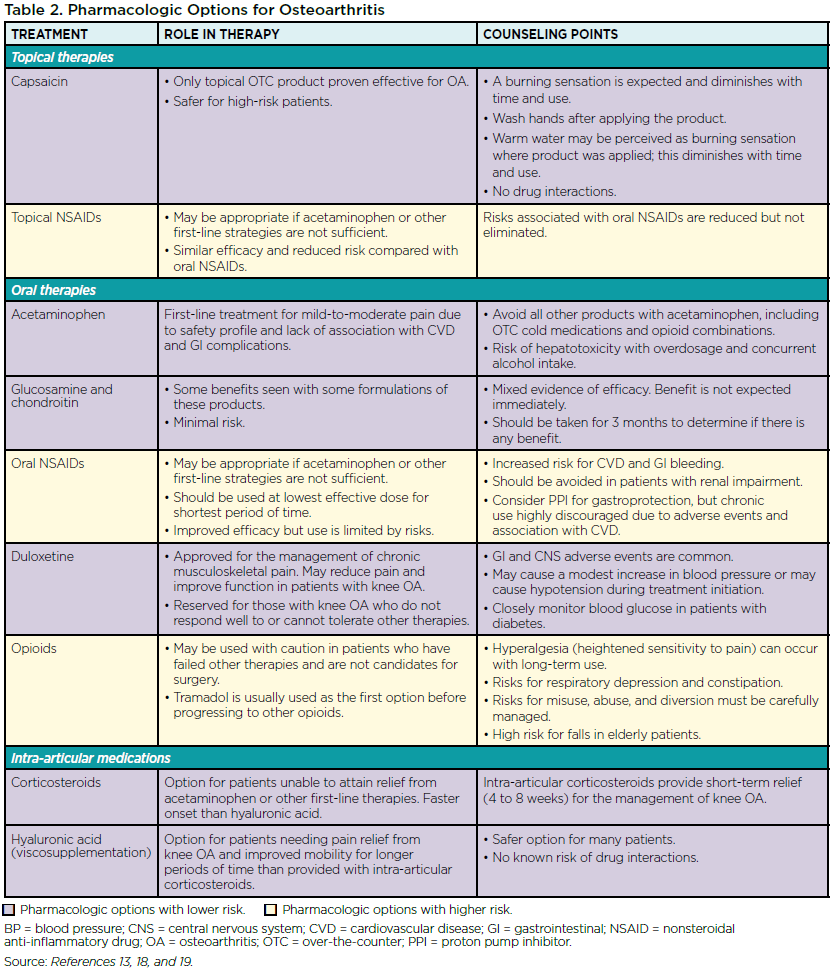

As a chronic painful condition, OA often requires a multifaceted approach that addresses a range of patient needs to maintain function and mobility. Components of treatment may include:

- Appropriate pain management to attain goals of improved function, health, and quality of life.

- Exercise to help control weight and maintain balance and mobility.

- Weight loss, which is particularly beneficial for patients with OA because it reduces strain on weight-bearing joints, and obesity itself is a cause of inflammation that can contribute to OA.6

- Educational programs and ongoing support.9

Many tools and resources are available to provide education and support for patients with OA. For example, links to useful resources from the Arthritis Foundation are available at www.arthritis.org/toolkits/arthritis-pain. Additionally, pharmacists can use motivational interviewing (MI) strategies to guide patients toward engaging in behaviors that will help them achieve their treatment goals.

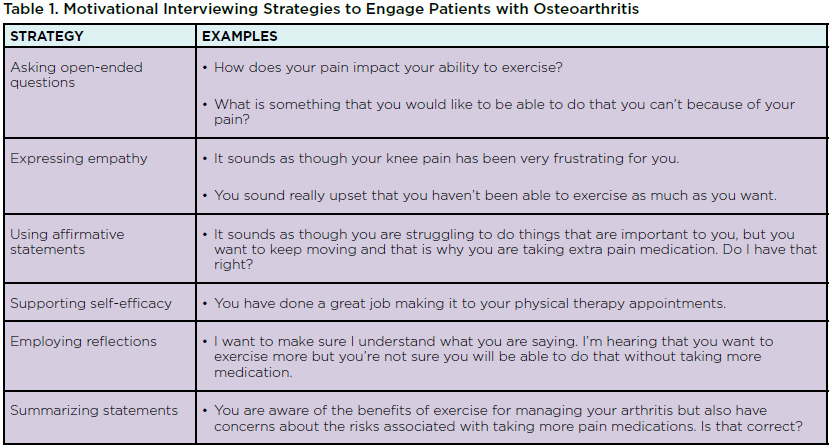

MI uses a patient-centered approach that acknowledges the patient’s expertise about his or her problems and empowers the patient to develop intrinsic motivation.10 Self-motivation is crucial when considering the importance of exercise and weight-loss in care plans for OA. Examples of MI strategies that pharmacists can use are shown in Table 1.

- Self-management programs and education

- Weight loss, if body mass index ≥25

- Joint protection (splinting)

- Range of motion exercises

- Low-impact aerobic exercise, including aquatic exercise

- Strength training

- Appropriate footwear

- Physical therapy

- Walking aids/assistive devices

- Balneotherapy/thermal agents

- Acupuncture

- Boring MA, Hootman JM, Liu Y, et al. Prevalence of arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation by urban-rural county classification—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:527-32.

- Parmalee PA, Tighe CA, Dautovich ND. Sleep disturbance in osteoarthritis: linkages with pain, disability, and depressive symptoms. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67:358-65.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults—United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:421-6.

- Wang H, Bai J, He B, et al. Osteoarthritis and the risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39672.

- Chung WS, Lin HH, Ho FM, et al. Risks of acute coronary syndrome in patients with osteoarthritis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:2807-13.

- Berenbaum F. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:16-21.

- Satariano WA, Guralnik JM, Jackson RJ, et al. Mobility and aging: new directions for public health action. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1508-15.

- Marra AC, Cibere J, Grubisic M, et al. Pharmacist-initiated intervention trial in osteoarthritis: a multidisciplinary intervention for knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1837-45.

- APhA Foundation. Expert Panel on Osteoarthritis and Chronic Pain. June 15, 2016. Available at: http://www.aphafoundation.org/osteoarthritis-and-chronic-pain. Accessed July 5, 2017.

- VanBuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2014;37:768-80.

- Bartels EM, Juhl CB, Christensen R, et al. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD005523.

- Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JW, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1125-35.

- Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:465-74.

- Horváth K, Kulisch A, Németh A, Bender T. Evaluation of the effect of balneotherapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hands: a randomized controlled single-blind follow-up study. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26:431-41.

- Lee PG, Jackson EA, Richardson CR. Exercise prescriptions in older adults. Am Fam Phys. 2017;95:425-32.

- Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD001977.

- Uthman OA, van der Windt DA, Jordan JL, et al. Exercise for lower limb osteoarthritis: systematic review incorporating trial sequential analysis and network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1579.

- Bruyère O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: a report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44:253-63.

- McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22:363-88.